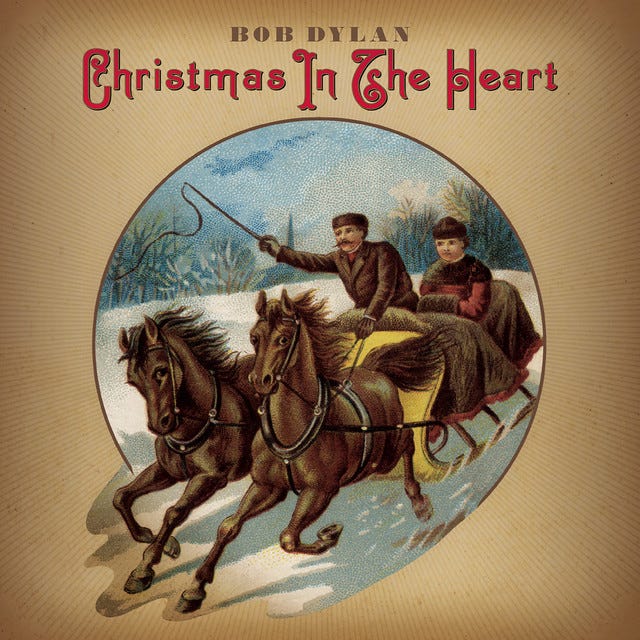

2009 was an unexpectedly big year for Bob Dylan. In April, with little warning he released his 33rd studio album: the accordion heavy Together Through Life, cowritten with Grateful Dead lyricist Robert Hunter.1 On May 24th, he marked his 68th birthday. His Never Ending Tour played 97 total dates across the year, including a summer tour of American ballparks with Willie Nelson and John Mellencamp. Then, in October, he released his 34th studio album: an LP of Christmas music entitled Christmas in the Heart.

Christmas in the Heart’s sole single was a riotous polka-klezmer version of “Must Be Santa,” indebted to an arrangement by the Texan “polka fusion” band Brave Combo that he had previously played on his satellite radio show, Theme Time Radio Hour.

Dylan’s version is almost identical to the Brave Combo version with one of the few differences being a change that he makes to the song’s fifth verse. In that verse, Dylan humorously adds eight post-1953 U. S. presidents to the lyric’s string of reindeer names:

Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen

Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon

Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen

Carter, Reagan, Bush and Clinton2

Anyway, like many late era Dylan gestures and projects, Christmas in the Heart was received partly as a joke—the kind of thing that you can picture people having brought up in casual dinner party conversation over the 2009 holidays in “can you believe it?” fashion. On Metacritic, CitH has a metascore of 62 on 17 critic reviews. Of those 17 reviews, Uncut and Q Magazine land the harshest blows.

Says Uncut, “[r]emoved from the comfort of his own musical constructions, [Dylan’s vocals] often sound like a collection of rasps, croaks and burrs optimistically corralled into what just might be words; Latin has never sounded more like a dead language than when Dylan sings in it on ‘O Come All Ye-Faithful.’” Ouch! Not too much better from Q Magazine: “alternating between the laughable and listenable, it's safe to say there's never been anything quite like the sound of him jollily croaking his way through ‘Here Comes Santa Claus’ or ‘Hark The Herald Angels Sing.’”

In contrast to those two reviews, one Chadwicked, writing contemporaneously for the immortal, gone-too-soon website Tiny Mix Tapes, rated the album 4 out of 5 stars, perceptively seeing it as related to two previous 90s covers albums in the Dylan discography: “In keeping with releases like Good as I Been to You and World Gone Wrong, the album features Dylan exorcising the musical spirits of the land.”

1992’s Good as I Been to You and 1993’s World Gone Wrong are Dylan’s 28th and 29th studio albums of spare acoustic folk covers that he recorded in his garage in Malibu. Recovering from the excesses and missteps of the 1980s3 and, specifically, the career nadirs of 1988’s cutting room floor collection Down in the Groove and 1990’s star-studded but unsatisfying Under the Red Sky, Dylan—as he has been prone to do over the years—returned to the deep wellspring of traditional music to reorient his artistic compass. What eventually followed—his first LP of original songs in 7 years in 1997 with the Grammy-winning, Daniel Lanois-produced Time Out of Mind—vindicated that gesture and canonized the improbable late career comeback narrative4 that most people know about Dylan if they do care about or even know anything after “Tangled Up in Blue” or “Hurricane.”

If Good as I Been to You and World Gone Wrong are Christmas in the Heart’s antecedents, its succedent releases now have to be considered Dylan’s 2010s standards era trilogy: 2015’s Shadows in the Night, 2016’s Fallen Angels, and 2017’s masterful Triplicate. I have written at considerable length about my own reception and belated appreciation of the standards era in a recent piece, but let me just say here that the appearance of those releases in the 2010s and my own love for them over the last several years has contextualized CitH in a new way. I have begun to see the Christmas album less as a silly novelty and more as yet another texture in Dylan’s wide-ranging discography that has come to include many different types of American song forms. Note the similarity in the way that Dylan speaks about the CitH material and the standards era material in separate interviews with Bill Flanagan in 2009 and 2017 respectively below.

Flanagan: Why do you think Christmas has better songs than other holidays?

Dylan: I don’t know. That’s a good question. Maybe because it’s so worldwide and everybody can relate to it in their own kind of way.

Flanagan: Very often when contemporary artists do Christmas records, they look for a new angle. John Fahey did instrumental folk variations on holiday songs, Billy Idol did a rock and roll Christmas album, Phil Spector put the Wall of Sound around the Christmas tree and the Roches did kind of a kooky left-field collection. You played this right down the middle, doing classic holiday songs in traditional arrangements. Did you know going in you wanted to play it straight?

Dylan: Oh sure, there wasn’t any other way to play it. These songs are part of my life, just like folk songs. You have to play them straight too.

Flanagan: Are you concerned about what Bob Dylan fans think about these standards?

Dylan: These songs are meant for the man on the street, the common man, the everyday person. Maybe that is a Bob Dylan fan, maybe not, I don’t know.

Flanagan: Has performing these songs taught you anything you didn’t know from listening to them?

Dylan: I had some idea of where they stood, but I hadn’t realized how much of the essence of life is in them—the human condition, how perfectly the lyrics and melodies are intertwined, how relevant to everyday life they are, how non-materialistic.

Dylan’s philosophical orientation to both the Christmas songs and the standards evinces a deep respect for the source material—a shockingly reverent stance if the only Dylan one knows is the speed-addled cultural insurgent of the mid-1960s. Instead, here we find a man paying significant attention to the past, and, in doing so, finding universal resonance in the cultural production of ostensibly alien and bygone eras. Christmas songs “are part of [his] life, just like folk songs” and standards “are meant for the man on the street, the common man, the everyday person.”

Sonic similarities between the two projects abound, too. As I have been revisiting CitH in the lead up to this year’s Christmas, I’ve been struck by Donnie Herron’s gorgeous pedal steel playing on Dylan’s renditions of “The Christmas Song” and “Silver Bells.” Herron’s liquid pedal steel would later be featured heavily in Dylan’s standards era arrangements, such as on aching tracks like “I Could Have Told You.”

Listening to CitH after the release of Dylan’s first album of original material post-standards era, 2020’s Rough and Rowdy Ways, has also been rewarding. Male backing vocalists are a rarity in the Dylan discography, but one can find them on two highlights from CitH and RaRW: “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” and “I've Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You.”

Though I do sometimes wish that Dylan could have recorded CitH post-standards era so that his vocal delivery could have been as softened and finely-tuned as it was on RaRW,5 there is also something oddly perfect about the tension created by his gravelly rasp as set against the holiday tracks’ immaculate period homage instrumentation and backing vocalists. I defer here, again, to Chadwicked’s tremendous 2009 review in which they note, under styles, that CitH can be filed alongside “[l]aryngitis-stricken carolers [and] tavern Christmas hymnals.” Amazing! Chadwicked also has this to say about Dylan’s 2009 voice: “His voice is his voice: damaged. It’s the voice of Bing in a smoky bordello, a crooner in a crack house. His voice is this: you are caressing a polished piece of wood (a mantle with stockings hung?), when suddenly your palm is punctured by a crack in the varnish — a splinter.” There’s a gruffness, a first-take rawness to Dylan’s vocals on the record. Indeed, the relatively ragged Dylan vocal performances6 that we find on CitH ground the material, keeping it from entirely achieving the status of frictionless holiday muzak. They remind us of the specific singer of the universal song—the person deeply depressed at Christmas (I’ve been there!), awed at the birth of the Christ child, or yukking it up envisioning an exoticized tropical Christmas.

As Chadwicked also astutely notes, CitH is also perhaps Dylan’s most materially political album. (That’s right, even moreso than The Times They Are a-Changin’.7) Dylan agreed to donate all the album’s royalties in perpetuity to the charities Feeding America in the USA, Crisis in the UK, and the World Food Programme. Though such a gesture could be easily written off as celebrity conscience laundering, Dylan wrote in the album’s press release with an urgency about the issue:

“It’s a tragedy that more than 35 million people in this country alone—12 million of those children—often go to bed hungry and wake up each morning unsure of where their next meal is coming from. I join the good people of Feeding America in the hope that our efforts can bring some food security to people in need during this holiday season.”

That Dylan made his Christmas album a vehicle for charity in perpetuity aligns well with his approach to the record thematically and musically. It is an album about universal good feeling, reflective stocktaking, and, above all, self and other-centered compassion. In other words—one might say—saving a place for Christmas in the Heart.

I discussed Together Through Life—specifically in the context of 2009 indie rock releases—a bit in my recent piece about seeing Dylan at Massey Hall at the end of October.

Poor Gerald Ford! Guess he just didn’t fit the rhyme scheme…

“Ugliest Girl in the World,” “Dirty World,” ummm whatever was going on for Dylan during the “We Are the World” video shoot. (Incidentally, a lot of bad “world”-related cultural content for Dylan in the 80s!

Funnily enough, it has now been 26 years since Dylan’s improbable late career comeback in 1997!

My partner has also (rightly) roasted me for attempting to mount a defence of CitH using this theory—that it could’ve been a very different album had he recorded it at a different time! lol

These are ragged Dylan vocal performances, but, honestly, they are no “Pay in Blood.”

With apologies to these guys, wherever they are.