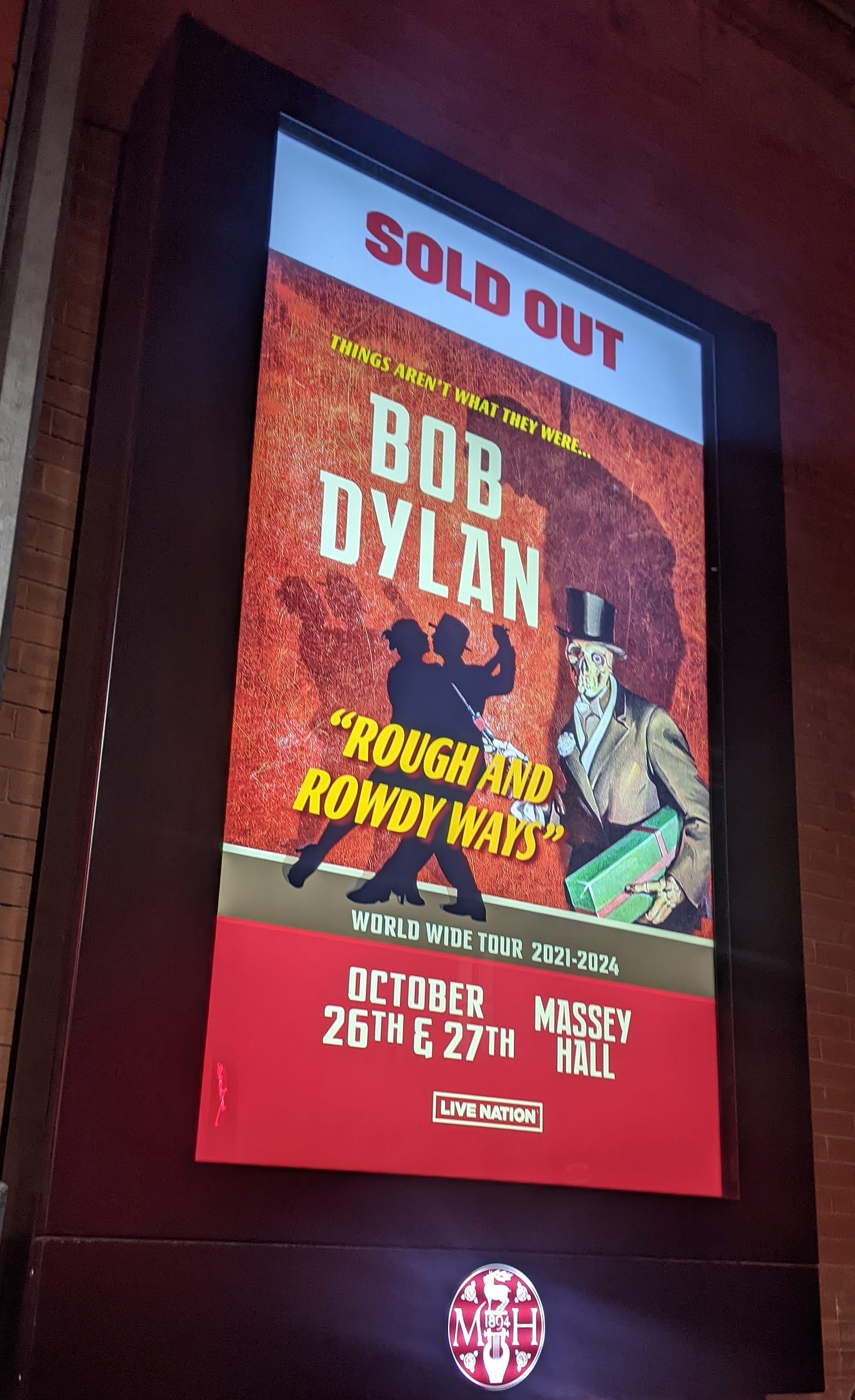

Thoughts on Bob Dylan Live in Toronto at Massey Hall, 27 October 2023

On Friday 27 October 2023, I saw Bob Dylan live and in concert on his Rough and Rowdy Ways World Wide Tour: 2021–2024 at Toronto’s storied Massey Hall. (I didn’t dare miss it!) I met up with a friend from grad school—a fellow hardcore Dylanhead, my friend Sandy, who graciously let me crash in his living room—and we took in a magisterial set from Dylan, his longtime bassist Tony Garnier, guitarists Bob Britt and Doug Lancio, drummer Jerry Pentecost, and pedal steel/lap steel/mandolin/violin player Donnie Herron.

I have been a Dylan fan since I was 13 years old when, one night, I found my parents’ vinyl copy of Blood on the Tracks in their record collection and decided to stay home and listen to it instead of going to a school dance. What I related to in Blood on the Tracks as an eighth grader I can’t say exactly, and it’s humorous now to think back to me skipping out on snowball dancing and the opportunity to win a raffled VHS copy of Pirates of the Caribbean to listen to a wounded album created by—as recently described by Ian Grant of Jokermen podcast—“the most divorced man of all time.”

Whatever it was that I found in the music, it struck a deep chord with me, and I spent the better part of my early-to-mid teens completely immersed in Dylan’s classic 1962–1975 period. The early folk albums (1962–1964) were an easy sell for me and made immediate sense, as I had been raised in a family circle that regularly potlucked and sang as a group throughout my childhood. I had probably been hearing songs like “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right”—though, admittedly, in their poppier Peter, Paul and Mary arrangements—since I was in utero.

In particular, Dylan’s hallowed electric trilogy—coinciding with the unfathomably fecund period spanning March 1965’s Bringing It All Back Home through June 1966’s Blonde on Blonde—consumed me as a teenager who had vaguely literary ambitions. I wore some version of this shirt regularly throughout high-school, and wrote my own dreadful Tarantula-indebted blank verse poetry and songs for my first girlfriend.1 I have vivid sense memories of blasting the white-hot rendition of “Tell Me Momma” that opens the electric disc of The Bootleg Series Vol. 4: Bob Dylan Live 1966, The "Royal Albert Hall" Concert on the bus on my Panasonic Shock Wave at what must’ve been like 7:30 a.m. in grade 9. I bought Andy Gill’s Classic Bob Dylan, 1962–69: My Back Pages along with a raft of (then amazingly affordable) used Bob vinyl from a local used bookstore.2 Scorcese’s Dylan documentary No Direction Home arrived when I was fifteen and I watched it religiously. I learned, printed off, and filed in a big D-ring binder probably close to 100 Dylan songs from Eyolf Østrem’s essential free chord website dylanchords.com. Sitting in my bedroom at night, burning incense, I would listen to the entirety of The Bootleg Series Vol. 6: Bob Dylan Live 1964, Concert at Philharmonic Hall—still probably my favourite of the Bootleg Series if I was pressed to pick one—grinning at Bob and Joan Baez flubbing lyrics in “Mama, You Been On My Mind” and losing my own mind at how someone was able to write a song like “It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding).”

As I grew older and began exploring a wider range of music via the rich 2000s music blogosphere and online publications like Tiny Mix Tapes, I drifted from Dylan and lost touch with his current work. As an example, 2009’s Together Through Life was basically about as uncool as an album could come that year, what with its pre-distressed cover typography, stock photo artwork, and vigorous use of David Hidalgo’s accordion playing on many tracks. (Pitchfork Best New Music this decidedly wasn’t). My attention was elsewhere that year, fixated on the likes of Merriweather Post Pavilion, Veckatimest, and Bitte Orca. 2012’s Tempest was intriguing at the time, but I recall getting fatigued at Dylan’s then gravelly rasp of a voice, especially across 68 minutes of material that included a 14-minute song about the sinking of the Titanic (“Tempest”).

The most estranged I became from Dylan’s output was likely in the 2015–2020 period where he recorded and toured three separate albums of popular standards, many of them previously sung by Frank Sinatra: 2015’s Shadows in the Night, 2016’s Fallen Angels, and the aptly titled 2017 triple album, Triplicate. When Shadows… was first announced, I remember thinking it was laughable and a bit embarrassing. I did eventually warm to it when it came out, and it was a record that my mom and I bonded together over, but when Dylan doubled and then tripled down on the standards era with the release of the successive albums in 2016 and 2017, I—and I think quite a few others—had lost patience. He had released 167 minutes(!) of standards material across 2 years. As a gesture, it only worked to mystify many fans who had first come to Dylan for his inimitable writing style. Now, suddenly he was singing “Some Enchanted Evening,” “Skylark,” and “Stardust.”

This is perhaps a tangential point that would be worth treating at length in a separate piece, but it is also worth considering the cultural climate in North America that coincided with Dylan’s standards era releases. When Donald Trump was unexpectedly elected to the United States presidency in fall 2016, the world of culture suddenly took on enormous significance overnight. Remember the sentiment that at least there would be good punk music under Trump? Remember the pressure and associated anxiety that charged discussions with worried liberals—particularly from fall 2016 through winter 2017—about what you were reading, watching, and listening to to try to make sense of… well… it all basically? Dylan’s standards records did not play well in this cultural climate, and, instead, appeared—at least to me—fundamentally escapist and inherently conservative. If Trump wanted to MAGA, Dylan seemed to want to MASGA: Make American Songs Great Again.

This is obviously a ridiculous and uncharitable reading of the standards era records now—particularly after I have come to adore this period of Dylan’s career with the benefit of some hindsight—but I can’t deny how out of step and unserious the albums felt in the face of one’s early impressions of the Trump administration. What many people wanted from art in that period—urgency, direct political confrontation, foregrounding of identity-political matters in the face of something like the baldly hateful Executive Order 13769—Bob was not providing. In retrospect, this was yet another instance where people longed for a previous version of Bob that was no longer there. And, really, what would a “The Times They Are A-Changin’” or “Masters of War” in 2016 even have amounted to if not just a sclerotic re-tread of a Time Life nostalgia version of the 60s? Dylan was too smart to go there again, and, at that stage in his career, he had a longer view of the country’s arc, of how brutality, dispossession, and immiseration were much more prevalent in the fabric of American history than #Resistance Liberals would ever allow themselves to come to accept. Besides, other people were writing protest songs and putting them up on Bandcamp for people to buy in a righteous moment of anger and then never listen to again.

Two (related) cultural artifacts worked to return me to the Dylan fold in 2020: Dylan delivered a late career masterwork in Rough and Rowdy Ways, and Ian Grant and Evan Laffer undertook a refreshing longform examination of Dylan’s discography on their absolutely essential Jokermen podcast. The brilliance of Grant and Laffer’s project on the Jokermen podcast was to begin from 1967’s John Wesley Harding and to move forward exhaustively across the remaining Dylan discography from there. Grant and Laffer assumed (rightly) that 1962–1967 was, essentially, canonical and completely overdetermined by the weight of history and critical analysis. Instead, they wondered about the succeeding 56 years(!) of the man’s career. They also brought a much-needed sense of humour to so-called Dylanology (though they, I’m sure, wouldn’t dare refer to themselves as Dylanologists). Where Dylanology has historically been the province of either completely obsessive weirdos who want to buy Bob’s baby high chair in Hibbing or humourless, self-serious, logorrheic commentators,3 Grant and Laffer simply didn’t take themselves or the music too seriously, shooting from the hip in how they felt about certain albums and periods, being more than willing to (lovingly) poke fun at Bob, and working in occasional references to mustard,4 Mario Kart, and Super Mario Sunshine.

Rough and Rowdy Ways, Dylan’s first album of original compositions since 2012’s Tempest, arrived in June 2020 after the release of “Murder Most Foul”—Dylan’s 17-minute song about the assassination of JFK—in March 2020. I first listened to RaRW on the roof of the house that my sister was renting at the time while drinking a beer in the sun. By June 2020, early pandemic malaise had fully set in—the days blurring into one another—and I was using Friday album releases to motivate myself to get through entire weeks of lockdown. Underemployed, depressed, and worried about my mother—who was trying to forge ahead with a bone marrow transplant amidst all of that time’s seismic disruptions to health care—sitting on my sister’s roof and drinking was one of my main pastimes. I had found an early leak of the album, and, of course intrigued by “Murder Most Foul,” tentatively delved in. On first listen, I was absolutely blown away. Dylan’s voice had seemingly improved since Tempest, revived by the years of standards crooning, and the songwriting and musicianship on display was so deep and tasteful. Jack Frost’s production skills had improved markedly since debuting all the way back on 1990’s Under the Red Sky. Most markedly, Blake Mills’ guitar parts were intricate and stunning across the album.

The two standout tracks on the record for me were the gorgeous ballad “I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You” and the cryptic closer “Key West (Philosopher Pirate).” As Ian Grant has recently articulated on his Bob Dylan Revisited YouTube series, the power of “I’ve Made Up My Mind…” lies in the intentional ambiguity of who the titular “you” actually is: is it a lover? Dylan’s audience? The road itself? Perhaps all of those at once? Musically, the song quotes a gorgeous melody from Jacques Offenbach's barcarolle “Belle nuit, ô nuit d'amour” from his 1881 opera Tales of Hoffmann. “I’ve Made Up My Mind…” is perhaps the tenderest song in the Dylan discography, almost shocking in its fragility and utter prettiness. Somehow, the same man who wrote “Positively Fourth Street” and “Idiot Wind” also wrote this.

“Key West” is harder to get one’s head around, no matter how many times you try to parse it. It’s a stately song, luxurious both in soundscape and in its unhurried lyric. On the album recording, Donnie Herron colours the track with beautifully restrained accordion playing while Dylan unspools some of the most striking lyrics of his late period:

Wherever I travel, wherever I roam

I'm not that far before I come back home

I do what I think is right, what I think is best

History Street off of Mallory Square

Truman had his White House there

East bound, West bound, way down in Key West

Twelve years old, they put me in a suit

Forced me to marry a prostitute

There were gold fringes on her wedding dress

That's my story, but not where it ends

She's still cute, and we're still friends

Down on the bottom, way down in Key West

I play both sides against the middle

Trying to pick up that pirate radio signal

I heard the news, I heard your last request

Fly around, my pretty little Miss

I don't love nobody, give me a kiss

Down on the bottom, way down in Key West

Though I absolutely hate to think in these terms: if, indeed, Rough and Rowdy Ways may be the closing chapter to Dylan’s illustrious discography, “Key West”—and “Murder Most Foul,” which follows it in the album’s sequencing but is notably set apart on its own dedicated disc—would be a fitting end to his collected poetic corpus. These are profound, but strangely oblique songs, not about something, but all referring to many things at once. Is “Murder Most Foul” about the death of 1960s progressivism at the hands of something far more deep-rooted and malevolent in the American soul? Sure, maybe. Could also be a guy listing a whole bunch of songs he likes. What the hell is “Key West” about? A retrospective song actually narrated by Kennedy’s assassin? A mellow paean that Dylan himself is singing about the vast geographical reach of his own poetics arriving at a kind of final resting place in the Florida Keys? A spiritual sequel of sorts to 1997’s epic album closer, “Highlands”? Maybe. But, like other songs in Dylan’s late career style, it could also be a series of exquisite images and dense references to other musical and lyrical intertexts.

Seeing Dylan and his band on the Rough and Rowdy Ways World Wide Tour—particularly as rumours have been swirling about the potential end of his touring life when this tour ends in 2024—was a special experience. I had seen Bob two times before in the mid/late-2000s and each of those experiences had been alienating: a combination of awful live venue sound, and Dylan’s penchant for radically rearranging his classic material to the point of making his most famous songs completely unrecognizable to the uninitiated. I have memories of seeing Dylan in Regina in 2012 and realizing about halfway through a song, when a stray snippet of a lyric somehow became sensical to my ear, that it was “Tangled Up in Blue” or “Highway 61 Revisited.”

At the risk of sounding like a ridiculous apologist here, I have always found Dylan’s commitment to touring secondary and even tertiary markets in North America to be moving. Perpetual road dog that he has been since 1988, Dylan clearly believes in playing as often as he can and in as many places as he can, and this has manifested in an undying commitment to playing places that you’d be surprised he’d play. The last time Bob played my home province of Saskatchewan back in 2017, he threw in a date in Moose Jaw.5 Back in 2004, he and Willie Nelson embarked on a 23-date tour of minor league American ballparks, which took them to places like Wappingers Falls, NY,6 and Sevierville, TN.7 On the current tour, around his two-night stand at Massey Hall and his date at Places des Arts in Montreal, he played dates in Rochester and Schenectady. The downside to this dogged commitment to service the cultural hinterlands in the Old, Weird America has been that he has often played venues with subpar acoustics—the worst of the lot probably being the boomy hockey arenas that I saw him in twice—that have left his sound muddied and dull. Add to that his constant desire to reimagine his catalogue musically with the different touring bands that he has helmed, and you have a challenging set of circumstances,8 especially for more casual audiences expecting fan-service live shows like they regularly get from other aging rock icons like McCartney and Springsteen.

On the Rough and Rowdy Ways World Wide Tour, Dylan has chosen to play smaller theatres with far superior acoustics and a decidedly more intimate ambience, indicating, perhaps, that he views presenting the Rough and Rowdy Ways material live differently than his standard Never Ending Tour dates.9 It was for this reason that I knew I had to see him at Massey, and my intuition was immediately confirmed by the power of seeing him again in such fine form and in such a perfect venue.

Much has been made in the Dylanologist community about his choice of covers on this tour. In Indianapolis, Bob whipped out an obscure 2008 John Mellencamp song, “Longest Days,” bringing some of those in attendance—and even me via bootleg audio—to tears. In Cincinnati, he played a song by Dwight Yoakam, “South of Cincinnati.” He has also been regularly including Grateful Dead covers in his set, pulling out classics like “Truckin’,” “Brokedown Palace,” and “Stella Blue.”

In his 2019 thesis, Matthew Lipson writes about the concept of what he terms “living archivism” in Dylan’s late period work. Admittedly, I haven’t carved out time to read this entire, fascinating piece of writing, but I’ve been unable to stop thinking about this concept since I first found Lipson’s work. As my friend Sandy said over lunch the day after the show, Dylan’s late career work has a fundamentally modernist bent to it, specifically a modernist relation to the cultural archive. Songs, song forms, lyrics, melodies—these are all constantly being recombined and played with in later-period Dylan songs from around 2001’s “Love and Theft” onwards to sometimes mystifying, oftentimes stunning effect.10

Standards era Dylan took this notion of archivism to an even greater length, however, by using Bob’s own cultural production and—at that stage—iconicity as a performer to restore songs from the Great American Songbook to cultural memory and the cultural record. Consider, for example, Dylan’s own December 2014 statement upon the announcement of his first standards album, Shadows in the Night:

“I don't see myself as covering these songs in any way,” Dylan said in a statement. “They've been covered enough. Buried, as a matter a fact. What me and my band are basically doing is uncovering them. Lifting them out of the grave and bringing them into the light of day.”

The irony and, of course, tremendous poignancy to this “uncovering”11 project was that Dylan was reanimating, revivifying song forms that—as a speed-addled cultural insurgent in the mid-60s—he had helped to oust from the cultural consciousness in his pursuit of that “thin, wild, Mercury sound.” As mentioned above in my earlier discussion of the standards era records, this poignancy was something that I missed almost entirely when the string of records were first released from 2015–2017.

To my mind, the covers portion of the Rough and Rowdy Ways World Wide Tour plays a similar role to this standards era archivism: part of the power of hearing him cover a song is now in hearing Bob Dylan adding that song12 to his own, boundlessly expansive archive. Since at least “Love and Theft,” Bob has been playing with the cultural archive, but now—as we are faced with the possibility of his career’s end or, at least, it winding down—his own work has become an archive that interfaces with the larger cultural archive, and whole songs osmose between the two in strange and profound ways. Any song can suddenly become a Bob Dylan song, and maybe it always was but you simply didn’t know it yet. Imagine being Josh Ritter and hearing that Bob had unexpectedly covered a song that you wrote in the stairwell of your college dorm 25 years earlier.

In Toronto at Massey Hall on 27 October 2023, we got a cover of the Dead’s “Brokedown Palace.” The night previous, he had played “Stella Blue.” Hilariously, though fans had been buzzing about which Lightfoot13 or Robertson song he might play, he indulged neither fantasy. In perfect, Dylanesque fashion, he denied the tony Toronto cultural elite14 and rich boomer Dylanologist tourists their bespoke moment.15

Setting aside that humorous denial, my breath was knocked right out of my frame by the first notes of “Brokedown Palace.” It was a gentle rendition very similar to the one above from Milan.16 When you hear Dylan cover something like “Brokedown” or “Stella,” you are reminded, instantly, of the commonality that he must see between late Dead lyricist Robert Hunter’s work and his own.17 Dead songs often have the feel of being outside of time—of perhaps even being mistaken for traditional songs themselves—emerging out of some giant cabinet of curiosities of archetypical American iconography. Hunter, in his poetics, did a very similar thing to Dylan in that he absorbed forms from the archive but then wrote “new” songs that felt that they also belonged in, or came from that archive. For example, how does someone even begin to write a song like “Ripple” or “To Lay Me Down” when it has the feel of a song that has always existed, and, therefore, would never have needed to be “written”?

It is also worth mentioning and analyzing the setlist order where the changing cover comes: night after night right now, it seems to arrive after “That Old Black Magic” and before “Mother of Muses.” Notably, “Black Magic” is the sole inclusion from the standards era records in Dylan’s current set, and “Muses” is the song from Rough and Rowdy Ways that most directly addresses his own poetics, asking, “Mother of muses, sing for me.” In a three-song span in these sets, I believe that Dylan is telling us something about songs and also his own 60-plus year career as an American songwriter.

In “Black Magic,” a gesture is made toward the archive, or, rather, the archive is brought to life in front of us again, troubling its status as historical. In the cover slot, a song is selected from the broader archive and, immediately, included in Dylan’s own archive through performance. Then, in “Muses,” Dylan calls upon his muses for divine inspiration as he turns toward history. The key verse in “Muses,” according to this reading, is the third:

Sing of Sherman, Montgomery, and Scott

And of Zhukov, and Patton, and the battles they fought

Who cleared the path for Presley to sing

Who carved the path for Martin Luther King

Who did what they did and they went on their way

Man, I could tell their stories all day

History is yet another archive that Dylan uses, and there is a profound self-consciousness about history across Rough and Rowdy Ways, a sense in which Dylan may soon, himself, be added to that historical archive: “Mother of Muses, wherever you are / I've already outlived my life by far.” Until then, however, he continues to “tell … stories,” to reanimate the archive, to “uncover,” using—in Josh Ritter’s words—music as a “blessed traveller.”

Throwing out a bunch of this stuff on a recent trip home was a total head trip.

RIP Buy the Book in Regina, SK, Canada and its kind co-proprietor Chris Prpich who had endless patience for me as a teenager browsing in his store.

See, for example, the massive tomes published by Clinton Heylin.

As in: if this album were a mustard, what type of mustard would it be?

Population 33,890.

Population 5,522.

Population 18,662.

Consider Christopher Tessmer’s review for the Regina Leader-Post of Dylan’s 2012 show in Regina, SK, at the Brandt Centre which I attended where he notes, “quite a few in attendance were overheard after the set complaining that it was ridiculous how little of the vocals they could understand, and how many of the songs were rearranged versions of the tunes they had grown to love.”

The last time Bob had played Massey Hall was August 1992. (Here’s a bootleg from the 18 August show if you’re curious!)

One of my absolute favourites of these instances was Dylan lifting the melody completely from “Where the Blue of the Night (Meets the Gold of the Day)” as performed by Bing Crosby for his ballad, “When the Deal Goes Down” off of 2006’s Modern Times.

Dylan’s word choice here is absolutely fascinating, and I have thought about it at considerable length in relation to the standards era projects. Though he technically is covering the Great American Songbook material, he doesn’t view what he is doing as such, and, instead, he needs to undo the excess of covers—think, for example, of the trope of doing a covers album, Paul Anka, Tony Bennett, etc—that have caricatured and deadened both the gesture and the material over time.

We know from his recently published The Philosophy of Modern Song that this man adores songs, thinks deeply and imaginatively about them and that he always has.

Dylan has professed a longstanding adoration for Lightfoot’s songs, covering “Early Morning Rain” on 1970’s Self Portrait and the more obscure, gorgeous song “Shadows” live in Edmonton, AB, in 2012. According to Dylan’s own setlist archive, this was the one and only time that cover has been played. Wild!

Which apparently included Elvis Costello and Diana Krall, Broken Social Scene’s Kevin Drew, Blackie and the Rodeo Kings’ Tom Wilson, and Blue Rodeo’s Jim Cuddy in attendance.

And then two nights later he played Leonard Cohen’s “Dance Me to the End of Love” for the first time ever in Montreal lol.

Interestingly, no quality bootleg tapes from either 2023 Massey Hall show seem to have surfaced yet.

As a sidebar: it also makes it hilarious that they actually wrote some really awful work when they collaborated, such as the much-maligned “Ugliest Girl in the World.” But, hey, they did write “Silvio” and all of Together Through Life so there’s also that lol.