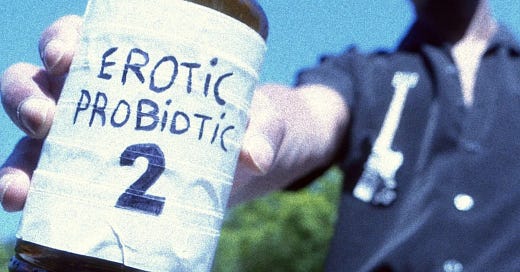

Thoughts on Nourished By Time's Erotic Probiotic 2

If you happen to have been extremely online on the Indie (Indeh?) Music Internet over (let’s say) the past 15 years, there are certain phrases from past iterations of The Discourse that, if mentioned, can send you careening back in time, memories of a previous version of life online—maybe even of yourself—arriving completely unbidden in a microsecond. Some of these phrases—usually associated with parodically niche music microgenres that were originally theorized on Tumblr and the formerly robust music blogging ecosystem1—can be communicated in shorthand via reference to certain canonical moments in semi-recent indie music culture.

For example, remember witch house innovators Salem’s (in)famous performance at Levi's® FADER Fort at SXSW 2010? Or when Rihanna appropriated seapunk aesthetics on SNL in 2012? What do you consider the top three chillwave releases, and tell me why they’re not Washed Out’s High Times, Neon Indian’s Psychic Chasms, and Toro Y Moi’s Causers of This? (in_this_household_we_dont_rate_memory_tapes_ascii_meme.jpg.)

Undoubtedly, one of the more regrettable microgenres of the late 2000s/early 2010s is what came to be known as PBR&B. PBR&B’s shallowness as a useful analytical concept is reflected right in its name: a mashup of a lazy reference to the beer of choice of the v-necked, moustachioed white hipster denizens of 2000s Williamsburg and Bushwick2 with R&B, a genre with a long, complicated past implicated in the history of American race relations and Black freedom struggle. Coined by music writer Eric Harvey in a tossed-off tweet in March 2011 in reference to The Weeknd,3 How to Dress Well, and Frank Ocean—figures that were all ascendant online at the time, and, I guess to be charitable to Harvey, were three acts not making guitar rock legible as “indie” to Gen X-indebted music critics—the term took on a (small) life of its own typical of the early 2010s music internet. It was used semi-ironically, employed to game SEO, and then it was problematized in thinkpieces as "R-Neg-B.” The basic idea was that PBR&B was R&B music made for a primarily white (hipster) audience.

In retrospect, what PBR&B seems to have been indirectly indexing but to have largely missed was more distressing materialist transformations in the American culture industry. Musician and writer jaime brooks has articulated many times across her perceptive work that Bain Capital’s acquisition of the iHeartMedia radio empire in 2008 marked a swift and distinct transformation in what came to be considered mainstream “pop” music in the late 2000s/early 2010s. At that time, rap and R&B were effectively pushed out of pop4 and so we were left with acts like imperial phase Katy Perry (maybe the biggest beneficiary of this era?), OneDirection, and fun. as a flimsy cultural imaginary whitewashed over the burgeoning diversity of twenty-first century identity and taste. Thinking about it now, maybe what PBR&B actually registered was a cultural appetite for contemporary Black music that was, at the time, subterranean to (and under-expressed on) the American mainstream pop charts, and so we saw it surface in hipster subculture.

Honestly, that’s probably giving the microgenre a little too much credit, though, and the best thing that happened to PBR&B is that it fell out of use as a meaningful descriptor. As streaming became increasingly hegemonic over the course of the 2010s, fans were allowed to enjoy music without handwringing about where exactly it fit within the broader genre ecosystem. Frank Ocean’s trajectory across the decade is illustrative of how PBR&B doesn’t and couldn’t hold up under even the smallest stress test. Ocean’s first release post-PBR&B coinage, 2012’s Channel Orange, was, if anything, firmly classicist R&B (with hardly a whiff of stale PBR to be had), and then it also contained the futuristic disco banger “Pyramids” to complicate matters. Four years later, by 2016’s ENDLESS and Blond(e), Ocean had moved definitively past genre as a meaningful analytical term, finally achieving his goal of being taken on his own terms as an auteur.

Dev Hynes’ work as Blood Orange in the mid-2010s—particularly 2013’s Cupid Deluxe, 2016’s Freetown Sound, and 2018’s Negro Swan—also comes to mind as music that would have received the PBR&B label had it been released slightly earlier, but, thankfully, I have no recollection of him being asked about the term regarding his mid-2010s work in anything that I read at the time. One reason for this may be that, by the mid/late-2010s, millennial culture writers had come of age and these critics were cognizant of how much more sense it made to ask an artist like Hynes nuanced questions about Blackness, identity, and queerness vis-à-vis a record like Negro Swan rather than rehashing tired genre debates.

The first time that I heard Nourished By Time’s debut LP, Erotic Probiotic 2, I was instantly transported back to that 2011 PBR&B moment as if against my will. Marcus Brown’s phenomenal new record sounds beamed out of that distinctly 2009-2011 period, its soft-focus homespun production fitting seamlessly in with chillwave’s post-2008 recessionary escapist sonics. (I, of course, then found it amusing and gratifying that Brown had professed a love for Toro Y Moi’s June 2009 tour CD-R on his entertaining Twitter a couple of months ago.5)

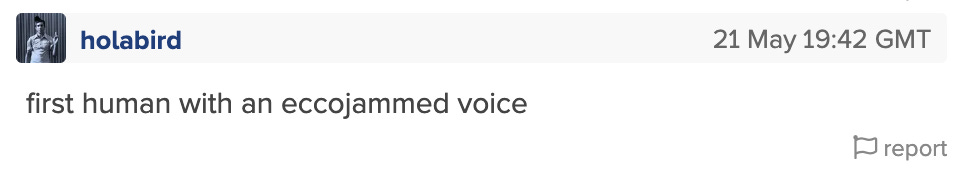

Another piece of online music ephemera related to Nourished By Time was this comment that I found in the Rate Your Music comment box on the page for the record:

The comment is an in joke in reference to Daniel Lopatin/Oneohtrix Point Never’s work under the Chuck Person project, which has proven to be massively influential for the vaporwave microgenre. Lopatin’s practice of eccojamming—or slowing down and reverberating loops of specifically evocative sections of (mostly 1980s) songs—has become a kind of vaporwave urtext. What user holabird is riffing on here is that Brown’s vocal work on Erotic Probiotic 2 sounds as if it has been eccojammed prior to even having been isolated and effected.

Anyway, turning away from the heavy music nerd intertextuality of it all and to the actual songs: the amount of heat that Brown brings on this short LP is amazing. Opener “Quantum Suicide” sets the tone for the record immediately, with huge bass and a steady drum groove anchoring his keys and evocative vocal work, reminiscent of late 80s/early 90s R&B.

“Shed That Fear” follows and summons the ghost of Arthur Russell in its verse vocal before transitioning into a massively catchy chorus: “You’ve gotta shed that fear / Of passing away / In order to live / Your life everyday.” Around the 3 minute mark, Brown returns the song to its opening Russellian mode, playing around with pitch-shifting his phrasing.

To my mind, the two immortal bangers on Erotic Probiotic 2 are “Daddy” and “The Fields.”

“Daddy” has strong song of the summer energy, its insistent beat and housey piano parts serving as a sonic bed for Brown’s effortless verses about competing with a woman’s sugar daddy for her affection only to lose.

I think “The Fields” will be my top played track of 2023, especially if my tendency to play it 3 or 4 times in a row persists through year end. It’s an up-tempo track. But it’s also a song permeated by deep melancholy and a sense of alienation at a world filled with capitalism’s everyday indignities that proffers sclerotic and oppressive organized religion as the only relief from a life of relentless exploitation. As the song’s catchy refrain goes (endearingly wonky “consumerizing” word choice and all):

Once or twice I prayed to Jesus

Never heard a word back in plain English

More like signs or advertisements

Telling me to be keep consumerizing

Church on highway intersections

Look at what the future’s been rejecting

Now the ends the end

The now and then

The fallen kings

The broken men

As Nourished By Time, Marcus Brown has made one of 2023’s most fascinating records. While listening to it, there is much to think about. You can trace the reference points of the LP’s sonic touchstones as I have done a bit above, or lose yourself in the immediacy of Brown’s strong musicianship and unique vocal presence.

Most of all, I’m glad that I get to luxuriate in and listen to Erotic Probiotic 2 in 2023 on its own terms without the weight of genre-based critical baggage represented by a term like PBR&B. Though much in the world has stayed the same over the past 12 or 13 years, this seems like one front on which some progress has actually been made. Admittedly, there are numerous problems with the political economy of music streaming platforms that we must address if we want anyone other than the ultra rich to be able to pursue a future career in music. One small silver lining, however, to the way that streaming has changed the culture industry is that less time and energy is now spent litigating who cultural production is for, who is or should be consuming something, etc. This is one small way in which the dream of the “celestial jukebox” has come to pass and feels a tad more authentically democratic. As Marcus Brown seems to be well aware, some things may actually be nourished by time.

Shoutout exp etc, shoutout Mutant Sounds, shoutout 20 Jazz Funk Greats, shoutout No Data, and many others.

Yes, the same type of shit that is apparently coming back as part of “indie sleaze” because we live in an historical moment that endlessly recycles the past due to “formal nostalgia,” as theorized by the late Mark Fisher.

It’s definitely wild to see Abel Tesfaye on this list in 2011 now that he is a Guinness Record breaking solo performer that effortlessly headlines the Super Bowl, but his early career trajectory was actually a bit rocky. Tesfaye released the cult mixtape trilogy of House of Balloons, Thursday, and Echoes of Silence all in 2011 shrouded in calculated mystery and white hot levels of hype. His first attempt at stardom, 2013’s Kiss Land, didn’t exactly hit, however, and it took Fifty Shades of Grey’s “Earned It” and the undeniable pop single “Can’t Feel My Face” in 2015 to finally rocket him to monocultural ubiquity.

Later to be vindicated, of course, by streaming metrics that would reveal rap music subgenres like trap as contemporary American youth culture’s true popular music. (Some view Migos’ “Bad and Boujee” going to #1 in January 2017 as a major milestone in shifts in how virality, quantified chart data, and pop music were understood together.)

Essentially, for those not invested in Deep Chillwave Lore, the takeaway is that the connection that I had immediately intuited was affirmed by Brown himself!