Thoughts on Gillian Welch & David Rawlings' Woodland

I think that I first discovered Gillian Welch and David Rawlings’ music in my Aunt Judy and Uncle Brian’s extensive CD library, which served as a significant musical influence in my formative teenage years. Sprawled out on the floor of their living room in front of hundreds of CDs and a multi-disc changer, I delved into a seemingly-endless collecton of incredible music: Robert Johnson, Iris DeMent, Buena Vista Social Club, Bobby Charles, Lucinda Williams, The Allman Brothers Band, Grateful Dead, Miles Davis, Townes Van Zandt, Dylan’s then “later-period” work like Good as I Been to You and World Gone Wrong and the star-studded The 30th Anniversary Concert Celebration, Rick Danko’s solo material, Lenny Breau, numerous amazing ‘90s/early-‘00s era tribute compilations like Poet, etc. Judy and Brian were hardcore music fans in the pre-streaming days when doing so was an expensive endeavour. Many of the discs they had were special orders from labels like New West, Lost Highway, Rounder, and Rhino—harder fare to find in the ‘90s than your typical Bob Seger’s Greatest Hits sold in your local gas station CD carousel.

While exploring Judy and Brian’s library with them, I had some of my first experiences spotting connections between records and artists, which has since become a huge part of my enjoyment of music. “This person—they kind of remind me of this other person!” “Wait a minute, she also plays on this other record!” “He cites her as an influence.” This kind of “associational listening” (for want of a better term)—a kind of listening that, it should be stated, is dependent on useful types of metadata like album liner notes and credits that are often completely absent in the streaming context—was undoubtedly foundational to how I came to experience music. We spent (and continue to spend) many treasured nights gathered around the speakers sharing music: laughing, crying, remembering.

One of the artists that I also distinctly remember encountering in their collection was Gillian Welch, whose first couple records had been released in Canada on the venerable folk/roots label Stony Plain that was started in Edmonton, AB.1 Gillian Welch’s music was striking and mystifying to me as a teen. It was austere and minimalist, simultaneously unrefined and pure, yet deceptively crafted if you looked a bit closer. Around the same time, inspired by early Dylan, I was digging more into traditional folk music like Harry Smith’s monumental Anthology of American Folk Music, and I remember thinking that a song like “Caleb Meyer” could’ve easily been on the Anthology. Welch—and her musical and life partner David Rawlings, who performed solely under Welch’s name in their early career days seemingly for branding purposes—wrote songs that felt completely out of time.

Welch’s first two records, Revival and Hell Among the Yearlings, proved to be a little too inaccessible to me, though I have come to love them in subsequent years. At the time, it felt like those records’ traditionalism made it such that I couldn’t get a handhold in them. I liked songs here and there like “Orphan Girl” and “My Morphine,” but did not fully appreciate the full records.

Once I moved on to 2001’s Time (The Revelator), ecstatically recommended to me at Judy and Brian’s, I finally fell fully in love with their music. I am only now realizing that the album has her first colour album cover, and that was definitely how it felt, to me, in contrast to the earlier records. What is there really to say about Time (The Revelator) that hasn’t already been said? It’s a perfect record, and a masterful tour of Welch and Rawlings’ different modes. The title track and “I Dream a Highway” are sprawling and almost psychedelic, despite their instrumental minimalism, in large part due to Rawlings’ stunning guitar work, which is, simply put, some of the best acoustic guitar work ever recorded. “My First Lover,” “Red Clay Halo,” and “Ruination Day Part 2” call back to the first two records, and Welch and Rawlings’ affection for more rugged blues forms. “Dear Someone” showcases Welch’s formal skill as a melody writer (very similar to “One Little Song” on 2003’s underrated Soul Journey), and the fact that, yes, fascinatingly, this quintessential “roots” musician actually went to Berklee and studied songwriting. “I Want to Sing That Rock and Roll” and “Elvis Presley Blues”, falling beside each other on the tracklist, winkingly interface with “rock,” yearning to play it—a common trope in Welch’s writing—and mythologizing one of its central characters. “I Want to Sing That Rock and Roll” is particularly a wonderful touch on Time (The Revelator) because it’s a live recording (from the Ryman Auditorium!), which showcases just how transfixing Welch and Rawlings are in the live context.

This leaves us with “April the 14th Part 1” and “Everything is Free,” easily two of the best songs of this century, despite being released a mere seven months into 2001. The former interweaves three catastrophic events that all occurred on April 14th in history—Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, the Titanic sinking in 1912, the Black Sunday dust storm of 1935—with the narrator’s stark observation of the detritus and squalor associated with the penury of being in a touring rock band. No matter how many times I’ve heard “April the 14th Part 1,” I can never quite get my head around it. It is an evocative song in the truest sense of the word that can be read differently on each listen. What is Welch doing drawing comparisons between these disasters, these “ruination days,” and the banality of a touring life in music? Does a musical life also cause unavoidable ruination? If so, is that ruination honourable or pathetic?

Speaking of ruination, “Everything is Free” is a stirring song that Welch wrote in response to the music piracy boom in the late-twentieth century that could also, without basically any updating, apply to the meagre compensation provided to “creators” in the streaming economy. Curiously, it has become one of her most famous songs, covered by others including younger artists like Father John Misty and Phoebe Bridgers. In it, Welch sings, “Someone hit the big score / They figured it out / That we're gonna do it anyway / Even if it doesn't pay,” laying out the basic exploitative economic conditions of present-day creative industries. Later in the song, though, Welch lands a devastating blow that also affirms her own autonomy as a writer and musician:

Every day I wake up

Hummin' a song

But I don't need to run around

I'll just stay at home

And sing a little love song

My love and myself

If there's something that you wanna hear

You can sing it yourself

“Everything is Free”’s final verse has always fascinated me. Instead of adopting the common rhetorical position—familiar to us from anti-piracy ad campaigns of the time—focusing on how ever-diminishing margins will end her artistic career, Welch forcefully asserts that she will continue creating art in private even if she is forced to get “a straight job,” but that her output will simply never be heard by wider audiences. If you never hear her work, it is, ultimately, immaterial to Welch, though, who throws it back at us in those last two lines: sing your own damn love song, then!2 Certainly, not every artist would feel emboldened to take this approach—radically asserting that they would doggedly continue to create in private due to an almost religious devotion to their practice after the total implosion of the creative industries—but I respect how Welch honours her creative impulse here, arguing that she will continue doing this thing regardless of how dire and exploitative everything else is or will become.

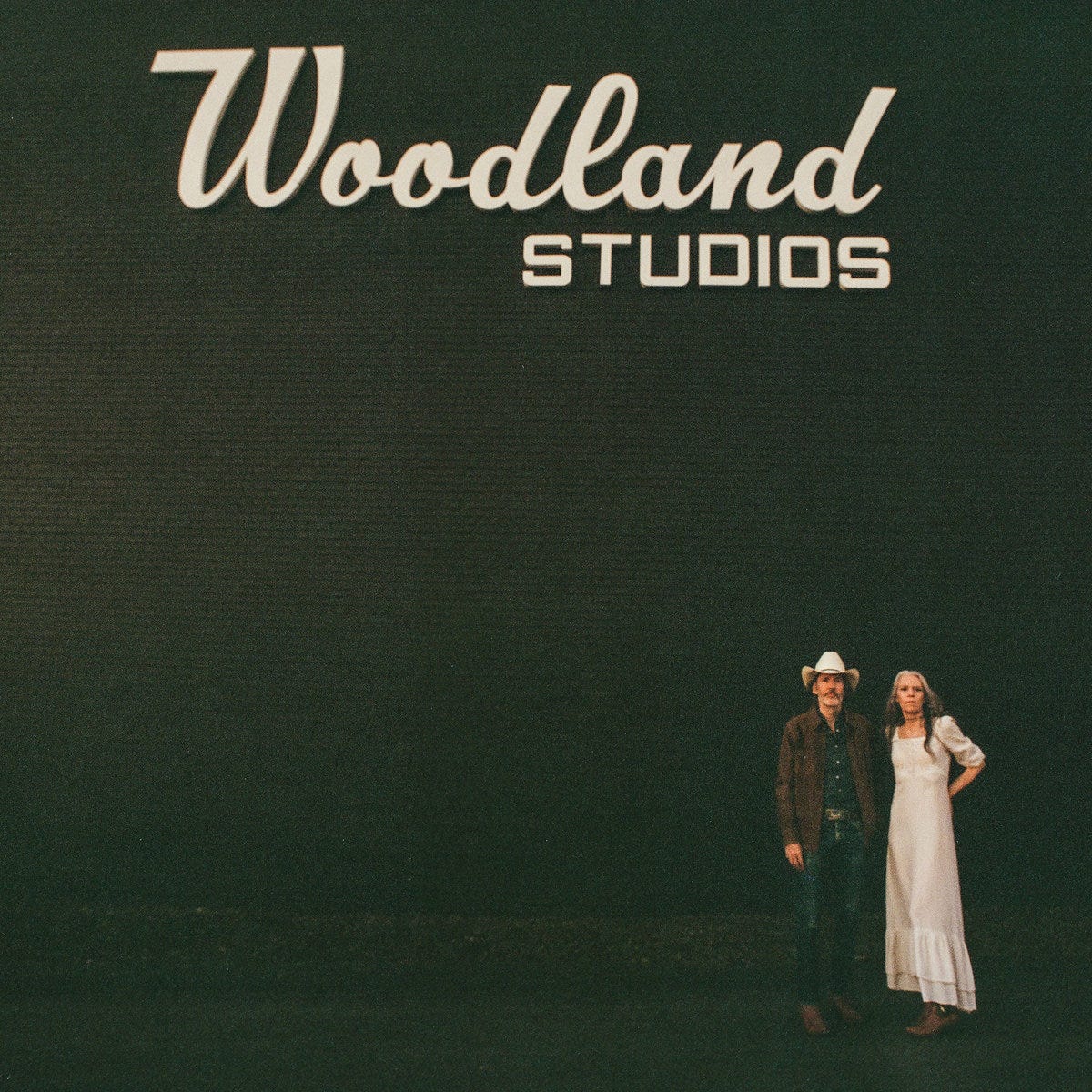

Welch and Rawlings’ new record, Woodland, is billed as their first release of original songs since 2011’s The Harrow & the Harvest. In July 2020, into those indistinguishable, uneasy days of summer 2020, they released an excellent covers collection, All the Good Times (Are Past & Gone) that went on to win a 2021 Grammy for Best Folk Album.3 Also in 2020, they released the second volume of their rarities series, Boots, and they have actually collaborated on other projects that have been released under David Rawlings’ name in the interim, like 2015’s Nashville Obsolete and 2017’s Poor David’s Almanack.

Setting all of that aside, however, there is something extremely special about Woodland, and some of that is related to the record’s name. Woodland is named after Woodland Sound Studios in Nashville, TN, a recording studio owned by Welch and Rawlings. Right before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in North America, in early March 2020, Woodland Sound Studios was hit by a tornado. Thankfully, due to Rawlings’ tireless efforts, the studio was eventually rebuilt across these past four years, and, having worked so hard to rebuild it, Welch and Rawlings were inspired to use it on Woodland. Says Rawlings in a recent interview with Jason Isbell for GQ,

once we got things going again, it felt like it was fun to use the studio for all you could use it for. We were just so appreciative that it was back, and that we’d redone it the way I’d always wanted it to be. It was one big room now, and the sound was really wonderful.

Across Woodland, one can hear Welch and Rawlings’ use of the studio in many stunning moments. The pleasure of these moments is heightened when one compares them to the musical austerity of their past discography. Opener and first single, “Empty Trainload of Sky,” introduces the studio touches subtly, sounding a bit like Dylan’s “Things Have Changed.” Behind the minor chords and tight vocal blend, you can hear the sound of a drum kit and bass playing, and, eventually, we get treated to pedal steel swells on the song’s bridge.

Second track, “What We Had,” is practically soft-rock adjacent with its strings, pedal steel accents, and tasteful drum work! Pre-release single, “Hashtag”—a moving musical tribute to their mentor, Guy Clark—uses French horn and strings in a painterly way.

Elsewhere on Woodland, Welch and Rawlings are in what we might call their “classic mode,” channeling the magic that exists between only their two voices and guitars. “Lawman”, (which dates back at least fifteen years ago in some form!), album highlight “The Bells and the Birds,” “Here Stands a Woman,” and the almost latter-period-Sufjan-esque “Howdy Howdy” are all in this vein.

Another notable difference between Woodland and past projects from these two is the fact that Rawlings sings lead on the album, which, to my knowledge, has never happened on a Gillian Welch project. He even takes lead for the entirety of “Hashtag” and the harmonica-accented “Turf the Gambler,” which sounds like it could’ve been pulled straight off of John Wesley Harding. Rawlings’ voice is not as natural of a singing voice as Welch’s, and, in a few rare instances, these moments where he is brought to the fore work to highlight some of his vocal limitations, but, largely, this is an exciting new direction for the duo to explore.

“North Country” and “The Day the Mississippi Died” are two of Woodland’s longer songs. The former is a comfortable, slower number that luxuriates in the guitar tone on offer from Welch’s (underrated) rhythm playing, Rawlings’ gentle leads, and notes of pedal steel that ease into the frame as the song progresses. “The Day the Mississippi Died” is jauntier in tempo and energy and coloured with sprightly fiddle. Thematically, though, the song seems to be at least partly about social alienation and environmental devastation, envisioning a scene where people are estranged from each other and the Mississippi has dried up:

Now the truth is hard to swallow, it's hard to take

But I do beliеve we've brokеn what we never knew could break

I'm just so disappointed in me and you

But we can't even argue so what else can we do

Honestly, I’m still getting my head around this song and the role it seems to be playing in the album. Though it may be clichéd to say at this point, Welch and Rawlings take their time with their music, and, as a result, their songs remain complicated to try to untangle. In the same GQ interview with Isbell that I linked above, Welch touched on this recently:

There's this funny thing that Dave and I talk about quite often, where the songs of ours that we like over the years, that sit well with us—in our opinion, they have multidimensionality. And they kind of, for us, have to have more than one layer. And that necessarily makes the answer to what's it about more difficult.

How wonderful it is to have more of Welch and Rawlings’ work out in the world for us to think with and about. Whether Woodland signals more to come from the duo in their rebuilt studio, or functions as a commemorative gesture on their part before going silent again is hard to say. What I do know is that music this good, this finely-wrought, can sustain—both artist and listener—for a very long time.

I would love to get the full story from Holger Petersen about how Stony Plain came to release Revival, Hell Among the Yearlings, and Time (The Revelator) in Canada. I’m sure it would be really interesting.

Though I’m not sure if this is intended by Welch here, ironically, this would return us to a kind of early folk music practice regarding the cultural status of music making. After the collapse of the creative industries, the only love song available to be heard might actually be one’s own, or, I guess—in a scenario not addressed by Welch in “Everything is Free”—a soulless one auto-generated by an AI bot?

It really can’t be overstated how amazing the covers album is. I’ve been returning to it recently in anticipation of Woodland and it is absolutely great. Props for covering two less covered Dylan songs: “Señor (Tales of Yankee Power)”(off of 1978’s Street-Legal) and “Abandoned Love” (an unreleased song from 1975 not released until 1985’s Biograph box-set)!